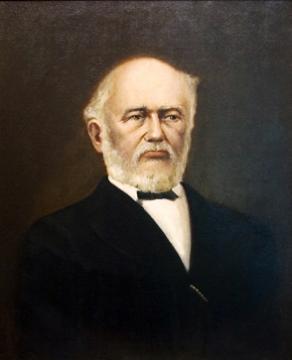

William & Mary President: Benjamin S. Ewell

Term Served: 1854 - May 11, 1888

Preceded by: John Johns 1849 - 1854

Succeeded by: Lyon G. Tyler 1888 - 1919

Before and during the Civil War, the university and many who taught, learned and led at William & Mary (including Benjamin Ewell) enslaved people and exploited them and their labor. Enslaved African American men, women and children lived and worked on these grounds and built many of the oldest parts of the campus. In 2018, the William & Mary Board of Visitors apologized for the university’s history with respect to the depredations of slavery and racial discrimination, expressed its deep appreciation for the contributions made by African Americans to the vitality of William & Mary now and for all time coming, and committed to continue efforts to remedy the lingering impact of past injustices. William & Mary’s Lemon Project and Hearth: Memorial to the Enslaved continue the ongoing work of discovery and reconciliation with the university’s role in perpetuating slavery and the legacies of racial discrimination.

Benjamin Stoddert Ewell presents a complex and challenging figure with respect to how William & Mary addresses its history with regards to slavery, race and the Civil War. Throughout his career, Ewell dedicated himself in service to William & Mary. He is credited with William & Mary’s survival following the turbulent political, economic and social upheavals during and after the Civil War. Ewell is a challenging figure because his strongest affiliations are not easily reconciled. Ewell’s family and Ewell himself enslaved people. He was a Unionist who argued against secession but also served in the Confederate Army. He favored enfranchising Blacks as voting citizens and advocated for educating whites and Blacks following the war.

William & Mary continues to recognize Ewell because of his resilience rebuilding the institution following two fires and a war and his relentless efforts to secure university finances – and because of the evidence that he supported crucial early steps to redress the depredations of slavery in Virginia. The complexity of this story underscores the still incomplete and uneven work of reconciliation with the legacy of those profound injustices.

Ewell was born in the District of Columbia and educated at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He arrived at William & Mary in 1848 as professor of mathematics and acting president until he was elected president in 1854. Ewell served as the interim president after Saunders and before Johns. While the Board of Visitors elected Ewell to the Presidency earlier in 1848, Ewell declined their offer, but agreed to stay on until the Board found another candidate. When the board failed to do that in a timely manner, Ewell resigned, forcing them to find another President. He stepped down on May 10, 1861 due to the Civil War but returned as president to reopen the university by 1867. Ewell officially reopened the college on October 1, 1869 with mostly his own funds, and stayed the president until William & Mary's closure again due to lack of attendance in July 1881. Inability to pay faculty salaries required suspending collegiate classes from 1881-1888, although grammar school classes continued. In 1888, the college was reopened with state funds, and Ewell was still the president until his resignation on May 11, 1888. Ewell continued to advocate for W&M until his death, including petitioning the U.S. Congress for funds for repairs after the 1862 fire. In large part due to that advocacy, in 1893 the United States paid William & Mary for damages sustained during the war. Ewell is buried on the north side of campus in a small cemetery begun during his presidency.

Ewell enslaved people, and though a Unionist, served as an officer in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. In 1861 he issued a general order of impressment that required enslaved people and freemen from the area – including those he formerly directed at William & Mary – to build earthworks to support Confederate forces on the peninsula. Some of those earthworks can still be seen in remnants of the battlefields southeast of Williamsburg.

After the war, Ewell sought partnerships with white and Black politicians and educators to build institutions that served a wide swath of Virginians, regardless of race. Popular stories about Benjamin Ewell recount him ringing the college bell as a symbol of William & Mary’s survival despite burned buildings and no faculty. In fact, it was his staff of now-freed Black men who performed this task, as noted below.

Ewell joined a bipartisan state coalition to fund institutions of higher education, bringing a state-approved normal program to William & Mary while steering Virginia’s Morrill Land Grant money to Virginia Polytechnic for whites and to Hampton University for Blacks. He authored appeals for federal funding for Blacks and whites. A visitor to William & Mary in 1883 notes his views in line with the Readjuster Party – in which Blacks were elected as party officers and, which among other actions, abolished the poll tax.

Ewell’s efforts to rebuild campus buildings, reestablish programs and hire faculty loom large in William & Mary’s post-Civil War history. Those efforts to keep William & Mary afloat fueled the longstanding myth that Ewell rang the college bell to signal that the institution had not closed through many years of hiatus. In reality, Ewell worked with familiar faces. He rehired now-free African American staff to cook, wash and labor, such as Edloe Washington, one of the men who rang the bell to signal the start of classes. Malachi Gardiner, who had served Benjamin Ewell since childhood and now identified as Ewell’s tenant farmer, drove his carriage and rang the bell to summon students to campus.

Benjamin Stoddert Ewell at William & Mary

- Professor of mathematics 1848

- Acting president 1848

- President 1854-1861

- College burns 1859, rebuilt 1859

- Resigned presidency during Civil War

- Served as an officer in the Confederate Army

- President 1865-1888

- College burns 1862, rebuilt 1867

- College reopens 1865-66

- Suspends college classes 1868-1869 (grammar school continues)

- Suspends college classes 1881-1888

- President emeritus, fundraiser/advocate, 1888-1894

Ewell is named or commemorated on William & Mary’s campus as follows:

- College Cemetery – established in 1859 to allow Ewell to bury his mother “in the rear of the Presidents garden.” Ewell is buried there with other family members. Stone marker to Ewell installed 1925.

- Ewell Hall (present day)

- Portrait, Presidents Gallery, Wren Building

Material in the Special Collections Research Center

- Benjamin Stoddert Ewell in SCRC Database

- Benjamin Stoddert Ewell in SCRC Digital Archive

- Addresses delivered at the unveiling of the tablet erected by the alumni to the memory of Benjamin Stoddert Ewell, LL. D., late president of the College of William & Mary : College chapel, June 21, 1899. in SCRC Rare Books - Association with William & Mary (LD6051 .W517 1854 C6)

- Report and address of Benj. S. Ewell / the president of the College of William & Mary to the Board of Visitors and Governors at their convocation in Richmond, on the 18th day of April, 1879.] in SCRC Rare Books -

Archives (LD6051 .W52 E9)

Further Reading

- Holly, L. Neal and Martin, Jeremy P. Leadership in Crisis: A Historical Analysis of Two College Presidencies in Reconstruction Virginia. February 14, 2012. From Penn State University Higher Education in Review, Volume 9, 37-64. 1 (accessed November 10, 2016).

- Benjamin Stoddert Ewell: A Biography by Anne West Chapman, The College of William & Mary, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1984. 8429747 (accessed December 13, 2018).